Bob’s Book Shelf – September 2020

September 30, 2020

By Father Robert Holmes, CSB

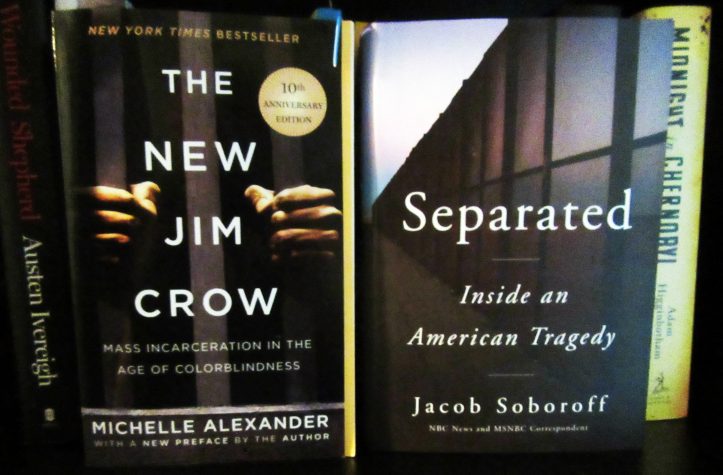

The 10th Anniversary edition of Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness could not be more timely. As Alexander says in her new preface, “Back in the 1980s and 90s, Democratic and Republican politicians leaned heavily on racial stereotypes of ‘crack heads,’ ‘crack babies,’ ‘super-predators,’ and ‘welfare queens,’ to mobilize public support for the War on Drugs, a ‘get tough’ movement, and prison building boom.” (p xv). The new, expanded anniversary version describes the relationship between the politics of mass incarceration and mass deportation and the role of prison profiteering in the expansion of these systems.

Jacob Soboroff, a national news correspondent for NBC and MSNBC, was among the first journalists to expose the reality of the systematic separation of desperate migrant families at the U.S. – Mexico border. In his book Separated: Inside an American Tragedy be tells the multilayered, complex story it took two years of reporting to research. Soboroff documents both the unspeakable horror migrants experienced in family separations but also how the Donald Trump’s American tragedy was able to happen.

The New Jim Crow – When slavery was abolished and as African Americans began the long march toward social and economic equality Southern states set up segregation legislation – the Jim Crow laws. The Civil Rights movement in the 50s and 60s brought the death of Jim Crow but with the Federal War on Drugs in the 80s the focus shifted from segregation to “getting tough on crime.” Large grants were made to police departments to enable the war and surplus military equipment made available. And results were demanded.

Alexander describes the mass incarceration that was created as a cage into which extraordinary numbers of black men are forced into. The entrapment occurs in three distinct phases.

“The first stage is the roundup. Vast numbers of people are swept into the criminal justice system by police who conduct drug operations primarily in poor communities of color. They are rewarded in cash – through drug forfeiture laws and federal grant programs.” (p 230). Using their own discretion they can stop, interrogate and search anyone they suspect. Although drugs were just as prevalent in white communities and on university campuses racial biases were granted free rein. Between 1980 and 2000 the number of persons incarcerated in U.S. prisons and jails soared from 300,000 to more than 2 million. Think prison pipeline. SWAT team drug raids on no-knock warrants in Minneapolis increased between 1986 and 1996 from 35 to more than 700. Think Breana Taylor!

Conviction marks the start of the second phase. Arrested, defendants are generally denied meaningful legal representation and are pressured to plead guilty by threat of a lengthy sentence into a plea bargain whether they are or not. “Almost no one ever goes to trial. Nearly all criminal cases are resolved through plea bargaining – a guilty plea by the defendant for some form of leniency by the prosecutor.” (p 109) In practice, it is the prosecutor, not the judge, who holds the keys to the jailhouse door. Conviction is the entry into the criminal justice system’s formal control – in jail, or prison, on probation or parole.

When they are released from the system they enter the final stage a “much larger invisible cage.” Labelled as ‘felons’ they will be discriminated against, legally, for the rest of their lives – denied employment, housing, education, and public benefits. Think of Florida where a referendum passed allowing those with a criminal record to vote if they completed their sentence and parole, but now the government has added the necessity of payment of debts due to the conviction as necessary as well, disenfranchising thousands who have no means of paying.

So how do we end mass incarceration? “We need an effective system of crime prevention and control in our communities, but this is not what the current system is. This system is better designed to create crime and a perpetual class of people labelled criminals than to eliminate crime or reduce the number of people under the system’s control.” (p 293) Clearly the War on Drugs must end with all the financial incentives that maintain it. Blindness and indifference to racial groups form the foundation of the system. Piecemeal, top-down reform will not move us forward. “We must flip the script. Taking our cue from the courageous civil rights advocates . . . join hands with people of all colors who are not content to wait for change to trickle down.” (p 321). Think Martin Luther King. Think Black Lives Matter.

Separated – Soboroff divides the story of his investigative journalism into three stages, beginning with Donald Trump’s stated goals in 2017 of stopping “the single-biggest problem along the southwestern border: drugs coming in and killing Americans.” (p 33). On the fifth day of his presidency he called for the end of “catch and release” of migrants crossing the border. Immigration violations became a criminal rather than a civil offence. Entire families were placed in detention centers. Family separation was being considered as a way to deter migration to the U.S. Soboroff met with Customs and Border Protection officials learning that the major drug traffic was not related to migrants and that families were being housed in shelters run by the Office of Refugee Resettlement.

Stage two begins with a bombshell revelation when, in June 2018, journalists were able to visit a shelter for the first time. It was in Brownsville, Texas in a converted Walmart store housing 1500 migrant boys ages 10 to 17. Soboroff described their situation as “incarceration.” He learned that 400 of the boys had been separated from their families and his reports outside the building went live on MSNBC and shocked the nation. Five days later, journalists were allowed to visit the Border Patrol Processing Center near McAllen, Texas. Inquiring about the family separation they were told that the order came down in May and already 1,174 kids had been separated from their parents. The report, once again, spread nationwide causing a nationwide outcry. Even Trump’s daughter, Ivanka, called on her father to end the family separation. He reluctantly did.

A California judge ordered reunification – separated families are to be reunited. This begins stage 3 of the story. But there is no record of where the parents were being detained (was this deliberate?) and 400 parents had already been deported without their children. A team was set up to work on it. It took a year and a half.

Throughout the reporting in each stage Soboroff humanizes the account by telling the story of Juan and his son José who fled danger from drug lords in Guatemala and sought asylum in the U.S. Separated and sent to different detention centers they were kept apart for four months. Even on reuniting they still faced deportation but were successful in their asylum appleal.

Categories

Discerning, a Vocations BlogGeneral News

Stirrings

Uncategorized

Separated: Inside an American Tragedy

reflections by Father Robert Holmes, CSB Jacob Soboroff, a national news correspondent for NBC and MSNBC, was among the first journalists to expose the reality of the systematic separation of […]

Read MoreLearnings from The New Jim Crow: Mass Incarceration in the Age of Colorblindness

by Fr. Robert Holmes CSB The 10th Anniversary edition of Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow could not be more timely. As Alexander says in her new preface, “Back in […]

Read MoreFather Bob’s Bookshelf

by Father Robert Holmes, CSB Two important reads during these “Black Lives Matter” days. My reflections are not so much a review of these books as a naming of a […]

Read More